A Short History of MongoDB

Unpacking the product strategy that shaped a winner.

Pete DeJoy | July 31st, 2020The Beginning

In 2007, Eliot Horowitz, Dwight Merriman, and Kevin Ryan had just had their adtech startup acquired by Google and were looking for their next challenge. The world was moving increasingly online, and these three found themselves extremely close to the epicenter of advancement in web development that would lead into the golden age of frameworks and toolkits for productive application development on the internet.

With that, they started 10gen, a company looking to build a web-centric platform-as-a-service using only open source components.

As they began to build the stack of tools that would amass to the 10gen PaaS, they stumbled across an interesting trend: up until that point, web developers had almost exclusively used relational databases as “one-size-fits-all” solutions for building web applications. Relational databases are great, but they had been around for 40+ years and were not well-equipped to handle the horizontal scale that they saw as a prerequisite to building applications for modern web-scale.

A lot of their frustrations were directed at the paradigm of vertical scale that had been popularized by commercial relational databases like Oracle, in which resources are thrown at a single instance of that database to add incremental bandwidth (💭 think 💭: one very, very big computer powering a single large store of information). At that point, the aggressive vertical scale of the database layer was generally accepted as a necessary evil to running a large application on the web; in fact, when AWS unveiled their MySQL-based database product (now RDS), they conveniently announced larger EC2 instances on the same day to prepare for the forecasted scale of the product’s usage.

The 10gen team saw the world a bit differently; they figured that, if their platform was going to be well-prepared to handle the challenges that the next-gen internet would impose, it would need a database that scaled horizontally (💭 think 💭: running the database across multiple smaller computers with different information living on each one, like a spreadsheet with last names A-L on my laptop and a spreadsheet with last names M-Z on yours, both of which can be simultaneously queried for users with the same birthday). This would be no easy feat; relational databases were the de-facto way to run web apps, and building a relational database that can scale horizontally is extraordinarily complex for a few reasons:

Their rigid structure is very difficult to change in production; when you change information across tables, you need to lock those tables simultaneously to ensure consistent updates. If I’m on a digital marketing team and want to A/B test forms without worrying about schema inconsistencies, I need a backend engineer to help me fit my data structure to my marketing database or need to perform a database migration to fit my updated data structure.

Distributed JOIN statements are really hard. I needed some backup from twitter to wrap my head around why exactly that is, but it turns out that, if certain data lives on a distributed set of nodes and can’t be joined in-memory, it has to be pulled to another machine coordinating the query to actually do the JOIN. There are some tools, namely CockroachDB, that are now doing some awesomely innovate stuff to tackle this problem, but in 2007 it was unchartered territory.

So they decided to build MongoDB: a horizontally-scalable NoSQL database that would run at the core of the 10gen platform.

Founder Eliot Horowitz recounts:

“MongoDB was born out of our frustration using tabular databases in large, complex production deployments. We set out to build a database that we would want to use, so that whenever developers wanted to build an application, they could focus on the application, not on working around the database.”

Pretty quickly, the market reacted and gave them indicators that they were not the only ones experiencing this problem; in 2008 they open-sourced MongoDB and began focusing all of their energy around the maintenance, development, and support of the project. Even until late 2011, the only product offerings that Mongo advertised on their website were support, professional services, and training for the open-source project itself:

The Rebrand

By the time 2013 rolled around, 10gen had started to dip its toes into a new collection of subscription products and offered a few additional features alongside their existing support, services, and training offerings. Namely, they had launched:

- Enterprise: A semi-abstract offering that seemed to be a separate MongoDB distribution with some enterprise-specific features. features. Namely, the enterprise distribution included Kerberos integration, an on-prem monitoring service, SNMP support, and additional testing.

- Monitoring: A free cloud-based service for monitoring MongoDB deployments from a centralized SaaS control plane. This presumably was the beginning of what would later become Mongo Cloud Manager- more on that later.

- Backup service: A cloud service for backing up and restoring MongoDB.

Soon thereafter, in late 2013, they rebranded their company to MongoDB Inc. Interestingly, with that rebrand, they combined their backup service and monitoring tool into MongoDB Management Service (MMS), which extended the scope of these offerings into new territories. Per its new definition, MMS would be “a suite of services for managing MongoDB deployments, providing monitoring, backup, and recovery to help users optimize clusters and mitigate operational risk.” It would be available as a fully managed Cloud service or as on-prem software included in an Enterprise subscription.

To put it simply, the team had decided to go all-in on the observability and reliability layer of running MongoDB at scale. MMS was a way to expose that layer to as much of the market as possible.

Licensing: Pt 1

Before continuing further, I just want to call attention to the fact that the MongoDB project was open-sourced under the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL). I won’t get too deep into the specifics here, but all you really need to know is that the AGPL allows for all of the things you’d expect from an open-source license except that the AGPL license must extend to all derivative works (new distributions, modifications, etc). This essentially means that any forks or projects that are built around MongoDB also must be fully open-sourced.

However, Mongo noted in their open-source documentation that “In some cases, we may have alternative licenses available for AGPL licensed code.” That gave them the creative freedom to “break the rules” and build derivative products that were not governed by the AGPL. As Ben Thompson pointed in his legendary AWS, MongoDB, and the Economic Realities of Open Source, this addendum formed the basis for MongoDB’s entire business.

Growing up

Moving into 2015, Mongo had simplified the packaging of its offerings significantly. While the services they offered still looked quite similar to their predecessors under-the-hood, they had received a product marketing facelift. The now described their products as follows:

MongoDB Enterprise Advanced: “The best way to run MongoDB in your data center. Supported. Secure. Certified. MongoDB Enterprise Advanced is a finely-tuned package of advanced software, support, certifications, and other services that’s designed for the way you do business.”

- This was very, very similar to v1 of their Enterprise subscription; an abstract set of products and services that help provide an extra layer of security and presumably help run mongo on-premises.

MMS: “The easiest way to run MongoDB. MMS is a cloud service that makes it easy for you to provision, monitor, backup, and scale MongoDB on the infrastructure of your choice”

- Interestingly, They repackaged MMS to be a cloud-only offering and decoupled the on-prem MMS tool into their Enterprise Advanced package. At this point, MMS was only optimized for AWS; it worked by installing agents into your database servers, which then would phone home to a controller that relayed metadata about the health of those servers back to the control plane.

This was an interesting subtle change in the presentation of their SKUs; I suspect that they saw industry trends pointing to a more effective strategy that bundled all on-prem offerings, including the MMS that had previously been offered independently as an on-prem deployment SKU, into their Enterprise subscription.

The Top-End Services Play

In early 2016, Mongo introduced a more service-heavy offering called MongoDB Professional. This product would go beyond the Enterprise Advanced subscription and provide more than just break/fix support. Per their website:

“MongoDB Professional gives you on-demand peace of mind. If anything ever goes wrong, the engineers who build MongoDB will help you resolve issues fast. We guarantee an initial response within 2 hrs for blocking issues, 24 x 365, anywhere around the world. MongoDB Professional goes beyond just break/fix support. Tell us where you want your application to go. We’ll tell you how to get there and how to avoid bumps in the road. Ask us for advice at any stage of your application lifecycle – from initial design to scale out.”

It’s certainly a bit abstract, but that description makes it sound more akin to architectural consulting, solution architecting around MongoDB, and top-tier support for the MongoDB project. One can extrapolate that, as MongoDB adoption became more widespread, the team started getting pushed for more hands-on knowledge sharing and solution-scoping than they had baked into their Enterprise Advanced subscription.

Their product marketing team also introduced this absolutely epic slogan that I think perfectly appeals to their entire TAM with a single sentence:

Welcome Atlas to the Party

In June of 2016, Eliot Horowitz put out a press release announcing MongoDB Atlas: the simplest, most robust, and most cost-effective way to run MongoDB in the Cloud.

If you’re familiar with the developer tool space, you’re undoubtedly familiar with the Atlas deployment model and how it’s changed the game in terms of industry perception of SaaS.

For those not familiar, imagine the simplicity of a fully managed SaaS offering with the security and latency-eliminating glory of an on-prem deployment: Atlas allows you to spin up a MongoDB server with a click of a button that peers to your VPC and runs in the same region and cloud as your data. Additionally, because it’s software that is run, managed, and administered by the Mongo team, they’re able to automate a lot of the operational nightmares associated with deploying and scaling a database; tasks such as database configuration, infrastructural provisioning, patches, scaling events, and backups are taken care of out-of-the-box.

For context, at the time Atlas was introduced, software deployment was generally accepted to be binary (with a few obvious exceptions). People either used tools:

- As SaaS: Software that is fully hosted by a vendor and does not require installation, with user access happening over the public internet. SaaS is generally easier to use, but large enterprises with big budgets are often SaaS-averse because of internal mandates that data can’t be exposed to the public internet.

- As PaaS/IaaS: Software that is designed to be deployed to a customer’s datacenter or cloud-based servers running in their VPC. This model is a bit more complex and requires more service work to deploy, but since it runs protected behind the customer’s VPC it often is more attractive to security-conscious enterprises.

Atlas provided a revolutionary hybrid; users could now get the ease of a SaaS offering with the security of a VPC-deployed piece of software. This would serve as an easy-to-use entry point for community Mongo users to start running Mongo in production systems and fuel a product-led go-to-market strategy that emphasized self-service and bottoms-up adoption.

Sequoia Gets Paid

On September 21, 2017, 10 years after its start, MongoDB, Inc filed its S-1 to prepare for an IPO. At the time, they had fundamentals that were quite compelling; 91% of their total revenue was pure software subscription, they had hit a 60% year-over-year revenue growth totaling $101.4 million at the end of the previous fiscal year, and they had acquired over 4300 paying customers including over half of the global Fortune 100s. In the S-1, they clearly delineate that their two main product lines are Atlas and Enterprise Advanced.

Now, keep in mind that the success of Atlas seems obvious in hindsight, but at the time of the IPO the growth potential wasn’t explicitly discussed. The below snippet is taken from their S-1 and suggests that, even though they had invested substantially in Atlas and saw significant product-market traction, they were still figuring out some pieces of the go-to-market strategy:

“We introduced MongoDB Atlas in June 2016. We have less experience marketing, determining pricing for and selling MongoDB Atlas, and we are still determining how to best market, price and support adoption of this offering. We have directed, and intend to continue to direct, a significant portion of our financial and operating resources to develop and grow MongoDB Atlas, including introducing a free tier of MongoDB Atlas to generate developer usage and awareness. Although MongoDB Atlas has seen rapid adoption since its commercial launch, we cannot guarantee that rate of adoption will continue at the same pace or at all. If we are unsuccessful in our efforts to drive customer adoption of MongoDB Atlas, or if we do so in a way that is not profitable or fails to compete successfully against our current or future competitors, our business, results of operations and financial condition could be harmed.“

Regardless, at the time of their IPO, they had over 1900 customers on Atlas and $2.1M in subscription revenue attributed to new Atlas adopters. That amounts to a annual contract value of $1,100, which is presumably significantly lower than that of their Enterprise Advanced tier. Still, they obviously saw massive opportunity: the word “Atlas” is mentioned 69 times, more than double amount of times that “Enterprise Advanced” is mentioned in the S-1.

The IPO proceeded and Mongo raised $192 million at a $1.2 billion valuation. The company’s shares began trading on October 19th, 2017 on the NASDAQ at $24/share.

What's better than a unicorn?

Well, 12 unicorns. Today, three years after their IPO MongoDB’s market cap is 12.6B and their shares are trading at $172/share. 700+% return 🤯!

Looking at year-over-year revenue since IPO, the growth is explosive:

So what’s happened between then and now?

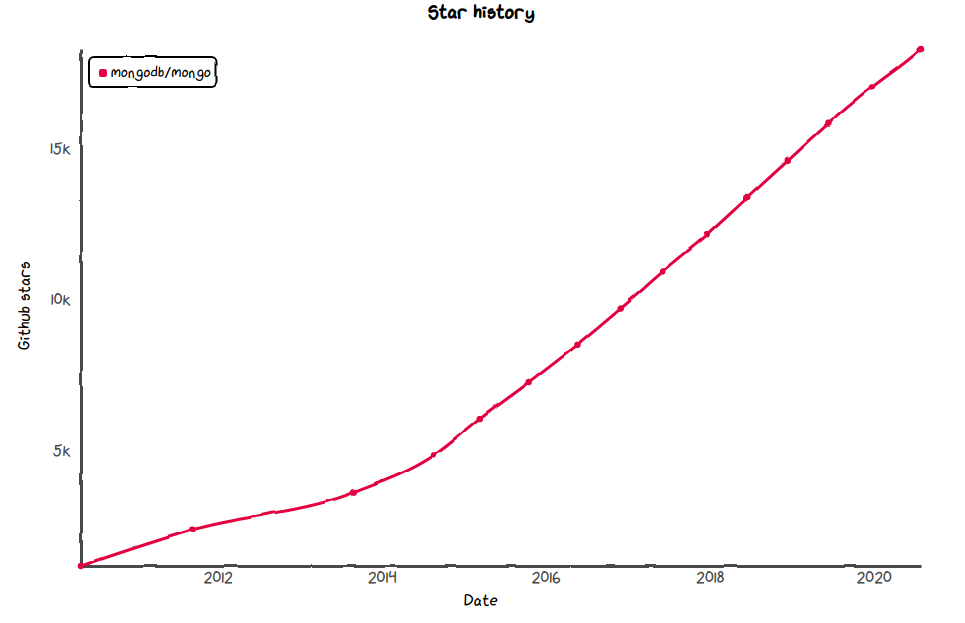

Well, first and foremost, the open-source MongoDB project exploded in popularity. A strong community presence, developer-first mentality, and strong bottoms-up product adoption strategy combined to drive developer adoption of MongoDB as an open standard for document-driven datamodels, which has paid dividends for long-term product-led growth. The below chart of the MongoDB repository's Github stars paints a picture of how open-source adoption can translate to strong revenue growth.

Now, zooming in on that star growth since IPO and superimposing it on top of quarter-over-quarter revenue:

Naturally there are many other factors contributing to revenue growth, but popularity of the open-source distribution is a good proxy for rate of bottoms-up product adoption, which correlates pretty directly to revenue.

Secondly, MongoDB Atlas happened, and it happened in a serious way. In 2018, Ben Thompson noted in one of his daily updates:

“Second, while most of MongoDB’s revenue at its IPO was driven by enterprise subscriptions, the fastest growing part of its business by far is MongoDB Atlas, its database-as-a-service offering. The company wrote in its most recent quarterly report:

We introduced MongoDB Atlas in June 2016. MongoDB Atlas is our cloud-hosted database-as-a-service (“DBaaS”) offering that includes comprehensive infrastructure and management of Community Server. During the three and nine months ended October 31, 2018, MongoDB Atlas revenue represented 22% and 18% of our total revenue, respectively, reflecting the continued growth of MongoDB Atlas since its introduction.

This understates things: Atlas was only 8% of total revenue last year, which grew 57% year-over-year; that means that Atlas itself grew 330% year-over-year, from $3.3 million to $14.3 million. Of course cost of revenue grew 68% as well, thanks to a $4.1 million increase in hosting costs (AWS wins either way), but particularly given the addition of a free Atlas offering, those costs aren’t out of line.”

In a daily update posted on June 10, 2020, he highlighted the revolution of his initial presentation of an understatement:

“Now that paragraph is the understatement: last quarter Atlas was up to 42% of MongoDB’s revenue, having grown 76% year-over-year.”

In last quarter’s 10-Q statement, Mongo claimed $130M in total revenue, with 42% of that revenue being attributed to Atlas. If I’m crunching the numbers correctly, that suggests that Atlas had done almost $55M revenue, up from $2.1M at the time of their IPO. Additionally, they claimed on their Q4 2020 earnings call (MongoDB Inc has a weird fiscal year that ends on January 31st) that they had over 15,400 customers on Atlas, up from 1900 at the time of the IPO. Just three years was all it took for over 25x revenue growth and 8x customer count.

Maybe less exciting, but still noteworthy, is that they seem to have deprecated their Cloud Manager/MMS offering (although it’s still available if you dig deeply enough on their website). This is interesting from a go-to-market perspective, as Cloud Manager was their last shred of true hybrid “bring-your-own Mongo” strategy. You would think that there are always folks that don’t want their deployment to be managed but still want a way to plug their existing servers into a remote monitoring setup. I’d hazard a guess that, as Atlas became more feature-rich, the Cloud Manager service became much less compelling for folks running MongoDB in the Cloud (Atlas only works with the three major cloud providers), as the maintenance, administration, and deployment piece introduced so much room for error that it no longer made sense to administer their own server. To put it simply, if you use Mongo Atlas instead of bringing your own Mongo deployment, you don’t need the observability features that Cloud Manager provides because you don’t need to deal with outages, patches, and uptime. Through that lens, Atlas becomes a much more compelling offering for anyone who wants to run Mongo in the cloud.

Still, there is a subset of the market that has been abandoned by the move away from Cloud Manager: the user running Mongo in an on-prem datacenter that wants to use a remote SaaS tool to monitor those instances. Abandoning that market segment feels like a choice that was likely influenced by internal compliance standards of enterprises running Mongo on-prem; if a team needs to keep their Mongo instance in their datacenter, are they really going to be comfortable exposing their database nodes to the public internet and sending metadata to Cloud Manager? Maybe in certain circumstances, but I’d bet that the majority of on-prem users (who also can’t use Atlas yet) would have compliance mandates requiring to host the management plane alongside those mongo instances within their private subnets, which is a feature included in the Enterprise Advanced subscription.

There’s also the possibility that the Mongo team has something in the works that will allow Atlas to interact with on-prem environments and they’re sunsetting Cloud Manager in preparation for that 👀.

The Winning Playbook

Much of this section is inspired and influenced by ideas presented by Ben Thompson’s analysis of the MongoDB playbook, but I’ll try to explain things in the context of this analysis and not repeat things that have already been said. MongoDB has had to make brilliant strategic moves to fend off competing cloud providers while explosively growing their user base and revenue. There are three major plays that they’ve made since IPO that have contributed to the monster returns for shareholders of the last three years.

Licensing: Pt 2

In early 2019, AWS launched DocumentDB (with MongoDB compatibility) (yes, the bit in the parenthesis is actually part of the product name!). At the time, they published the following on their blog:

“Today we are launching Amazon DocumentDB (with MongoDB compatibility), a fast, scalable, and highly available document database that is designed to be compatible with your existing MongoDB applications and tools. Amazon DocumentDB uses a purpose-built SSD-based storage layer, with 6x replication across 3 separate Availability Zones. The storage layer is distributed, fault-tolerant, and self-healing, giving you the the performance, scalability, and availability needed to run production-scale MongoDB workloads.”

If you’ll recall, MongoDB was initially governed by the AGPL license, which was quite permissive and left them vulnerable to this new AWS service; if AWS was able to just take the open source core and build a competing offering, MongoDB’s potential for differentiation (and thus existence) would be threatened in a serious way. To counter the threat, they got creative: they wrote their own new flavor of license called the Server Side Public License (SSPL). I won’t go too deep into what the license actually stated, but it basically told Amazon (and any other commercial reseller) that, if they wanted to offer MongoDB-as-a-service, they had to also open-source their entire stacks. This was quite an interesting play, as it stopped AWS dead in their tracks, but it also offended many open-source purists and officially made MongoDB, well, kind of not open-source. In fact, MongoDB withdrew the SSPL from the Open Source Initiave’s approval process and accepted their fate after Red Hat dropped MongoDB from it’s RHEL distributions. Some were really pissed that a publicly traded company could ever betray their hardcore open-source origins, but life goes on.

On October 16, 2018, the MongoDB Community Server releases began to be covered by the SSPL. Amazon’s DocumentDB still runs on the last available Mongo version governed by the AGPL and hasn’t had an update since this change was made.

You guessed it, MongoDB Atlas

Atlas is a revolutionary product that give users what they want: SaaS UX with beautifully effective VPC peering for low-latency, secure data storage.

Atlas again (well, kind of)

An interesting recent development is that Mongo is focusing on expanding Atlas further to be significantly more expansive; they’re taking a fully-integrated approach and building a BI layer, data layer, and data export layer as a strategic move to bring Atlas up the data stack.

On June 9th 2020 at the MongoDB Live conference event, the team announced some major product moves, including general availability of three new offerings:

A fully-integrated data lake for storing fully unstructured and non-transactional data, with additional features that allow users to query and analyze data across AWS S3 and Atlas using MongoDB Query Language. Fully serverless and priced based on total number of queries run.

2️⃣Atlas Search

A rich search engine for data living in Atlas, making it easier for data analysts to formulate complex MQL queries and allowing application developers to add full-text search capabilities to their apps without adding an additional searchable database like Elasticsearch to their stack.

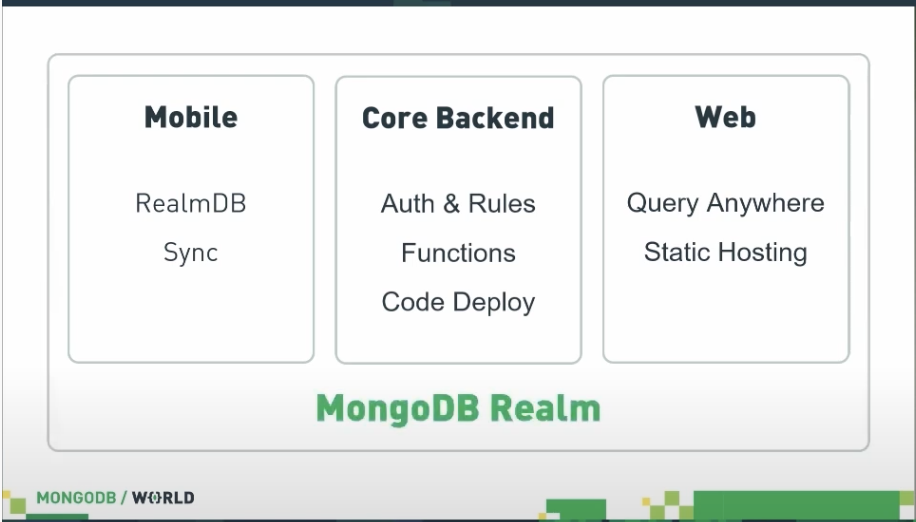

In May of 2019, MongoDB announced it’s 39 million dollar acquisition of Realm, an object-driven database for mobile application development. In their world keynote discussing the acquisition, their synergy is explained: Realm really set out to solve the same problem as MongoDB (application developers like working with objects rather than structured data) but in the mobile space. With that, they made the acquisition, hoping to keep Realm the same while also adding some new features that allow it to function as the cornerstone for modern mobile application development:

- Backups

- 💭 Think 💭: You switch (upgrade?) from an Android to an iPhone and maintain all of the metadata associated with your mobile applications, like your library of podcasts or your place in an audiobook.

- Cross-Device Sync

- 💭 Think 💭: Switching from your iPhone to your iPad mid workstream on a sketchpad app and having your iPad be ready to pick up where you left off immediately.

- Web-App Integration

- 💭 Think 💭: Using a web and ios app with the same centralized database so that you can have a clean and unified experience that translates from the browser to an iOS app.

To extrapolate into a higher-level context, Realm is a play to eliminate data silos in cross-platform application development. The below slide from their acquisition announcement sums it up perfectly (you'll notice they also teased some other features aside from the core three mentioned above; generally speaking, most of the them are features to eliminate boilerplate code and make developers more efficient):

Looking Ahead

With these three major announcements, Mongo is moving into uncharted territory and expanding their horizons into both the integrated data platform and mobile development spaces. They’re leveraging the explosive success of Atlas to become more than just a deployment and hosting solution for open-source: they're pushing to be the de-facto API for storing, accessing, analyzing, and updating both mobile and web application data.